Premium-to-Surplus Insurance Ratio

In Brief

- The premium-to-surplus ratio is an early warning signal for insurers and regulators.

- Staying under the 3-to-1 benchmark helps protect solvency, especially when venturing into new markets or lines of business.

- Even profitable growth plans can strain capacity if surplus is not strong enough to absorb underwriting and investment risks.

- Using reinsurance can help keep ratios in check, but the key is monitoring them closely and understanding what they reveal about your company’s financial health.

Insurance companies operate within a regulated market overseen by state insurance departments. To allocate regulatory resources effectively, these agencies rely, among others, on insurance ratios. When such ratios fall outside expected ranges, they act as warning signals, guiding regulators to areas that may require closer scrutiny. For insurers, these same ratios also act as early indicators of potential issues related to capacity, liquidity, and profitability.

Understanding Capacity

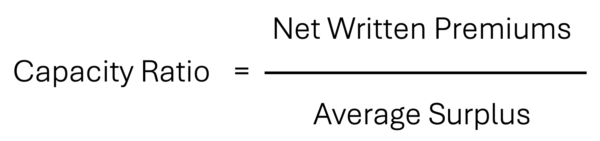

In this article, we focus on the capacity ratio, specifically the ratio of net written premiums to surplus.

Capacity refers to an insurance company’s ability to support growth. The core question is: How much premium growth can an insurer digest without compromising its solvency?

Solvency Indicator

Under statutory accounting concepts, the primary measure of an insurance company’s solvency is its surplus. As the term implies, surplus represents the residual value after subtracting liabilities from assets, and it is fundamentally the by-product of successful pricing, underwriting and investment management. Since both assets and liabilities are essentially management’s best estimates, the surplus functions as a financial cushion against unfavorable developments in those estimates. Such adverse changes can stem from two main areas: underwriting and investments.

On the underwriting side, accurately estimating anticipated loss and loss adjustment expense reserves is inherently difficult in the initial pricing of a product. If losses surpass the premiums collected for the associated policies, the insurance company must rely on previously accumulated surplus to fulfill its obligations to policyholders. On the investment side, market volatility, particularly in the stock market, can strain the surplus, testing its ability to absorb fluctuations while maintaining financial strength.

Rule of Thumb

The net written premiums to surplus ratio has been a regulatory tool for nearly a century. Its longevity speaks to its enduring relevance. Despite advances in technology, the calculation of this ratio has remained simple, with an established benchmark of 300%. In other words, the NAIC views a net premium-to-surplus ratio exceeding 3-to-1 as a potential cause for concern.

Why Limit Capacity for Profitable Business?

Some may question the rationale behind capacity limits when an insurer plans to write profitable business, typically defined by a combined ratio below 100%. The combined ratio measures the proportion of each premium dollar used to pay for losses and expenses. A combined ratio over 100%, such as 105%, means the insurer is spending $1.05 for every $1.00 earned in premiums.

However, the intention to be profitable does not always equate to the capability to do so. For an established insurer, writing premiums exceeding three times its surplus typically signals more than just organic growth; it possibly reflects expansion into new lines of business or unfamiliar geographic regions. Such ventures may fall outside the company’s historical experience. Rather than waiting to see how this business performs, the NAIC adopts a proactive approach to protect policyholders by identifying potential risks before they .

Utilization of Reinsurance

Reinsurance is an essential tool in managing an insurer’s capacity and maintaining a balanced premium-to-surplus ratio. By ceding a portion of gross written premiums, insurers reduce net written premiums, or the numerator of the ratio, while simultaneously decreasing the average policyholder surplus, the denominator. However, some reinsurance agreements provide for a ceding commission, which offsets some of the reduction in surplus by increasing it, thereby further reducing the net premium-to-surplus ratio. Industry benchmarks generally view a net premium-to-surplus ratio as acceptable when it remains below 3 to 1. Meanwhile, the Insurance Regulatory Information System (IRIS) ratios, used by state insurance regulators and the NAIC, flag a gross premium-to-surplus ratio as unusual when it exceeds 9 to 1.

We’re here to help

Insurance ratios do more than reflect past performance. They serve as forward-looking tools to highlight emerging risks. The premium-to-surplus ratio is one such critical indicator.

JLK Rosenberger, LLP is here not only to assist with calculating these ratios, but more importantly, to help interpret them and draw actionable insights for your insurance operations.